12. Toolkit

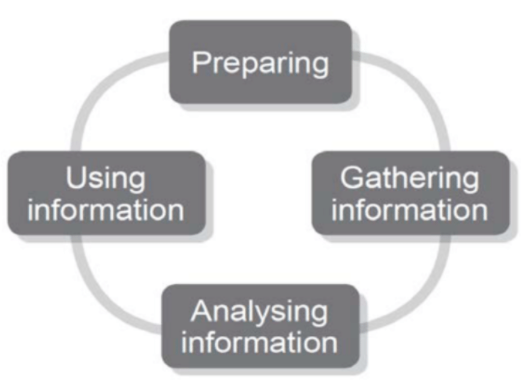

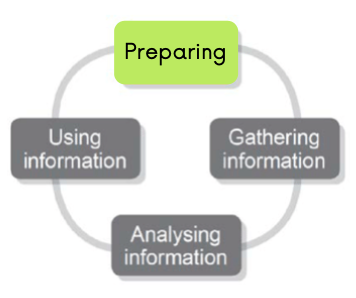

This Toolkit contains templates, tables, and checklists that you can use to help you at different stages in your evaluation (the list is not exhaustive).

- Evaluation and Development Cycle Checklist

- Tools to use in the Preparing phase of the evaluation

- Tools to use for Gathering Information

- Tools to use for Analysing Information

- Tools to use for Using Information

- Soft skills required in successfully conducting a youth entrepreneurship project

12.1 Difference between evaluation, monitoring and audit

Table 8: Monitoring, audit, and evaluation

|

Monitoring |

Evaluation |

Audit |

| Definition |

Ongoing analysis of project progress towards achieving planned results with the purpose of improving management decision making |

Assessment of the efficiency, impact, relevance, utility and sustainability of the project’s actions. |

Assessment of:

– The legality and regularity of the project expenditure and income

-Compliance with laws and regulation

-Efficient, effective and economical use of project funds |

| Who? |

Internal management responsibility |

External firms (research/consulting), internal specialists or self-evaluation |

Usually incorporate external agencies |

| When? |

Ongoing |

Usually at completion (ex-post) but also at the beginning (ex-ante), mid-term, and ongoing. |

Ex-post, completion. |

| Why? |

Check progress, take remedial action, and update plans. |

Learn broad lessons applicable to other projects and projects. Provides accountability and development. |

Provides assurance and accountability to stakeholders. |

Source: European Commission – Europe Aid Cooperation Office, 2004

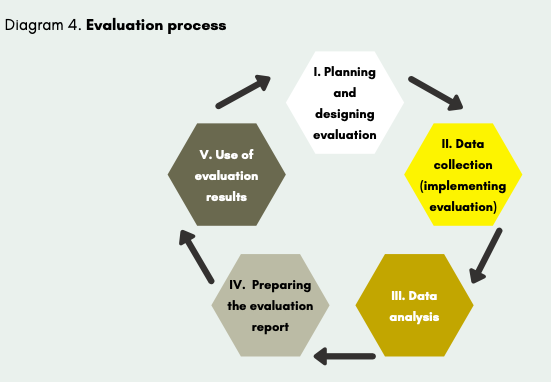

12.2 Evaluation and Development Cycle Checklist

Table 9: Evaluation and Development Cycle Checklist

| Addressed |

Yes (ii)

No (x)

Or Unsure |

|

PREPARATION

- What do you need to find out? What information will help you?

- Do you have clear and shared objectives for the evaluation?

- Is there a key evaluation question (or questions) to guide your evaluation?

- Have you identified the information that you need to gather?

- Do you have the skills and knowledge to gather it? Who will conduct the specific evaluation tasks? Is any external support needed?

- Do you know your stakeholders? Do you know if, how and under what conditions they can be involved in the evaluation? Do you know their expectations of the evaluation?

- Do you know what relevant information is already available?

- Do you know who can help you to find the information you need?

- Will each ‘partner’ have an opportunity to contribute to the evaluation?

|

|

|

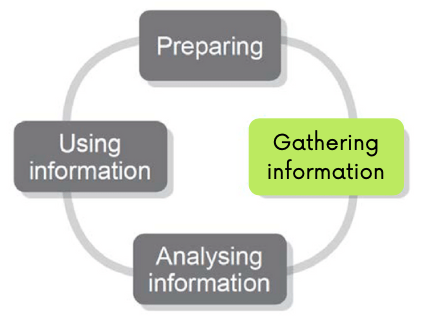

GATHERING INFORMATION

- How will you gather your information?

- Is your focus on gathering relevant information rather than a lot of information?

- Do you know with what methods the information is to be gathered (quantitative, qualitative)?

- Have you established a process for gathering information (existing and/or additional)?

- Who will collect it and how long it will take?

|

|

|

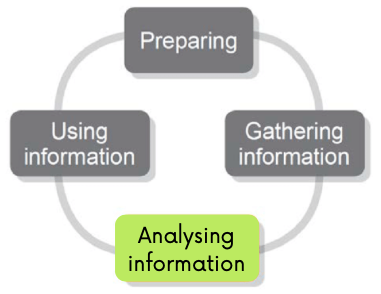

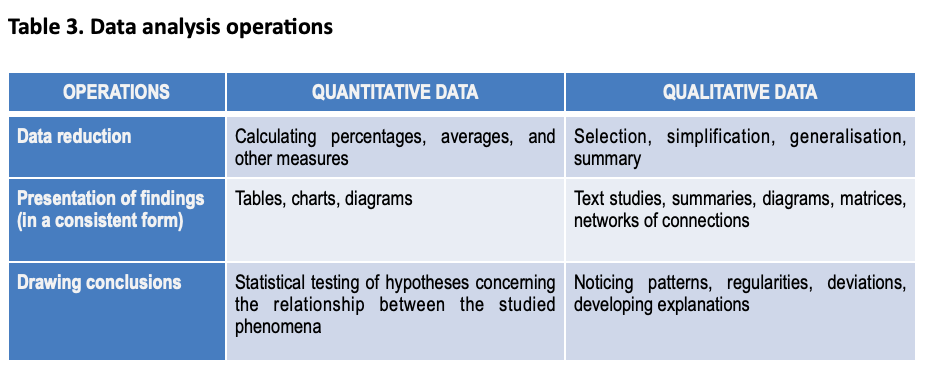

ANALYSING INFORMATION

- How will you analyse the data?

- What quantitative and qualitative data do you need to analyse?

- What analytical methods will you use?

- Do you have internal capacities to analyse the data?

- What does the information you have gathered tell you?

- Have you identified the main themes, patterns and trends (over time)? Are you clear about the main outcomes from your project?

- Are there any additional (i.e. unanticipated) outcomes from the project?

- Have you identified ways in which your Youth Entrepreneurship Support Action might be improved?

|

|

|

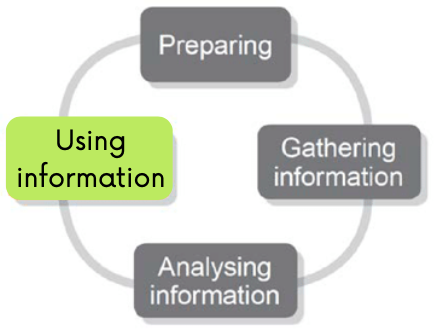

USING INFORMATION

- What can you learn from the evaluation results?

- Does your project respond to the needs of its recipients/local communities?

- To what extent the objectives and expected outcomes were achieved?

- What needs to be improved in our existing or future projects?

- What internal processes need to be improved?

- Have the communication channels and tools to share and promote what you have learned?

- Is there scope to expand or build on the project?

- Have you provided relevant feedback to your key stakeholders (answer to the questions of their interest in a written or verbal form)? Have participants in the relationship been invited to discuss the findings (where necessary)?

- Is the status of the project – complete, ongoing etc – understood? Have the stated objectives for the evaluation been achieved?

- Do you need to make changes to the project?

- Have you agreed how you will proceed next with the project?

|

|

Source: own elaboration

12.3 Tools to use in the phase of preparing the evaluation

12.3.1 Logical framework matrix

This is a tool with which you can reconstruct the logic behind the project you want to evaluate.

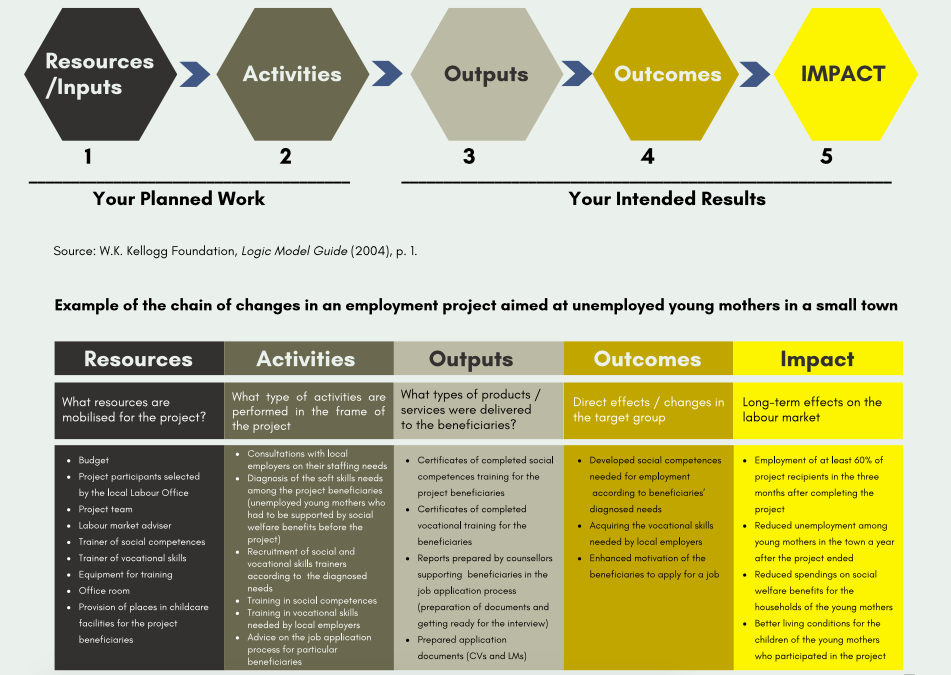

Figure 6: Logical framework matrix

Source: Department for International Development, 2007

The table below provides additional information on the elements of the Logical framework matrix.

Table 10: Difference between inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and impact

| Inputs/ resources |

Inputs are those things that we use in the project to implement it, including human resource, finances, or equipment. Inputs ensure that it is possible to deliver the intended results of a project. |

| Activities |

Activities are actions associated with delivering project goals. In other words, they are what the personnel/employees do in order to achieve the aims of the project. |

| Outputs |

These are the first level of results associated with a project. Often confused with “activities”, outputs are the direct immediate term results associated with a project. In other words, they are usually what the project has achieved in the short term. An easy way to think about outputs is to quantify the project activities that have a direct link on the project goal. For example, project outputs could be: the number of community entrepreneurship training carried out, the number of meetings with successful entrepreneurs or the number of educational publications published |

| Outcomes |

This is the second level of results associated with a project and refers to the medium-term consequences of the project. Outcomes usually relate to the project objectives. For example, it could be the improved level of knowledge about business-related topics or establishment of a start-up. Nevertheless, an important point to note is that outcomes should clearly link to project goals. |

Impact |

It is the third level of project results and is the long term or wider than project participants consequence of a project. Most often it is very difficult to ascertain the exclusive impact of a project since several other interventions can lead to the same goal. An example would be increased number of new businesses in the region, reduced unemployment or NEET rate in given a city. |

Source: Difference between inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and impact, 2013

12.3.2 Candidate Outcome Indicators

Indicators can be developed for various stages of your project. The figure 7 provides examples of outcome indicators of an Employment Training/ Workforce Development Program (The Urban Institute, What Works, n.d.).

Depending on the complexity and length of your programme, you can divide your programme into several stages and develop outcome indicators for individual stages of your programme.

igure 7: Example of candidate outcome indicators

Source: The Urban Institute, What Works, n.d.

12.3.3 Identifying your evaluation stakeholders

In any Youth Entrepreneurship Support Action there can be multiple stakeholders. Knowing your stakeholders can help you identify what kind of questions they would like to answer with the findings of the evaluation, in what form and when they may need it.

This stakeholder inventory is intended to help you identify who may be interested in your evaluation. Think about who needs to participate in the evaluation and who you will need to share the findings with so that the recommendations can be implemented.

Table 11: Stakeholder inventory

| Potential stakeholders of the evaluation |

Yes / No |

| Project recipients (who presently participate in the project ) |

|

| Graduates (recipients who already finished participation in the project) |

|

| Trainers |

|

| Mentors |

|

| Innovation Hubs (representative) |

|

| Business Accelerators (representative) |

|

| Private Equity and Venture Capital Firms |

|

| Project staff |

|

| Coaches |

|

| Angel Investors |

|

| Researchers |

|

| Local Administrative Authorities (representative) |

|

| Project partners |

|

| Volunteers |

|

| Other institutions executing similar projects (representative) |

|

| Local employers |

|

| Who else? (Add those that specifically apply to you) |

|

Source: own elaboration

Having identified your stakeholders, you should also think about the added value they could bring to your evaluation and their motivation to get engaged in the process. Based on this information you can decide about the type of information, key messages, as well as communication channels to be used.

Stakeholders can be categorized into 4 groups in terms of their influence, interest, and levels of participation in your project (Product plan, n.d.).

Figure 8: Power-Interest Grid

Source: Product plan, n.d.

- High power, high interest: the most important stakeholders. You should prioritise keeping them happy with your project’s evaluation – keep them informed, invite them to important meetings, ask for their feedback.

- High power, low interest: Because of their influence, you should work to keep these people satisfied. But because they haven’t shown a deep interest in your project, you could turn them off if you over-communicate with them. You should consider the frequency of contacting them and the amount of information provided.

- Low power, high interest: You will want to keep these people informed and check in with them regularly.

- Low power, low interest: Just keep these people informed periodically, but don’t overdo it.

12.4 Methods and tools to use in the Gathering Information phase of evaluation

Below you will find a number methods and tools that you could use in this phase of evaluation.

12.4.1 Identifying the appropriate methods to collect the needed information

Keeping in mind the purpose of your evaluation, identify the information collection methods and tools that will best suit this purpose. Summaries of each kind of the tool and method collection can be found in the section 9 “Gathering Information” above.

Table 12: Checklist to identify which methods can be used to collect needed information

| Method of data collection |

Which Information is most relevant to your purpose? |

Which Information will be easiest to collect? |

Which Information will you need some help with, to gather? |

What kind of information will you need? (eg. locating documents, identifying participants, analysing information, dissemination activities) |

Who can give you this help? (eg. a colleague, independent experts, a partner’s colleagues, project participants, an external evaluator) |

|

Desk research (document analysis/ review, such as reports, checklist,

diaries, journals and logs, testimonials, tests and other assessments) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Observation |

|

|

|

|

|

| Individual interviews |

|

|

|

|

|

| Focus Groups |

|

|

|

|

|

| Case Studies |

|

|

|

|

|

| Skill assessments (e.g., tests, self-assessments) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Survey |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: own elaboration

12.4.2 Personal potentials and objectives – self assessment tool

This tool is important in assessing the participant’s potential and objectives to find the right fit for them in the project and also be able to help them harness their potential. It is a guided enquiry where some of the participants (especially victims of forced migrations like refugees, immigrants, or people with disabilities) may not be able to understand all questions and may require guidance from the instructors to provide the required information.

These and personality assessments were inspired by tools available at the platforms mfa-jobnet.de and Psychometrics (visit www.mfa-jobnet.de and https://www.psychometrics.com) and with necessary modifications to fit this evaluation module, however the original source entails more tests that can help you assess the employability of a candidate.

Table 13: Self-assessment tool to assess personal potentials and objectives

| Education/Skills |

|

| In which areas have I been active in my life so far? What have I learned there? |

|

| What have I learned there? |

|

| What skills have I gained from this? What skills have I developed in my everyday activities? What general competencies have I gained through my professional and extra-professional experiences? |

|

| What professional or other training do I have? |

|

| What diplomas, certificates etc. do I have? |

|

| Which of my degrees are recognized in the country? |

|

| Which are not? |

|

|

Where have I worked before?

a) In the home country

b) In another EU state

c) In other countries

What other work experience do I have? |

|

| What in the training/work has particularly appealed to me, what have I been interested in, what have I been enthusiastic about? |

|

| What other qualifications do I have (e.g. language courses, computer training, driver’s license etc.)? |

|

| What skills and competences have I acquired in different places and countries? (Not only professionally, also in everyday life) |

|

| Where do I use them today? |

|

| What do I want to learn? |

|

| Which of my skills can I put to good use in the country I live in? |

|

| Are there areas in which I have completely different skills than current colleagues and friends? |

|

| Is there a profession would I like to take up now? |

|

| If no: What do I want to do for living instead? |

|

| What expectations and ideas did I have when I came to the country? |

|

| What is different than I expected? |

|

|

Is that

a) a disappointment?

b) a challenge for me? |

|

| How can the contacts I have be useful to me in implementing my ideas and plans? |

|

| Self-assessment |

|

| What have I successfully achieved in my life? |

|

| What have I always been particularly good at? |

|

| What has always been fun for me? |

|

| Which of my competences/skills relevant for my future professional life do I want to develop further? What do I want to become even better at? |

|

| What do I not like doing at all? |

|

| Which of my skills were particularly helpful/important/successful during my stay in this country? |

|

| External assessment |

|

| What abilities/strengths do others see in me? |

|

| What have I been able to inspire / impress others with? |

|

| For what have I received a lot of praise / recognition? |

|

| Work |

|

| Which 5 characteristics should a job have so that it fits me? |

|

|

How do I concretely imagine my future work?

Where? With whom? What exactly is my work? |

|

| What is my goal? |

|

| What can I do to achieve my goal? |

|

| What do I need help/support with? What exactly do I need? |

|

| Which difficulties/obstacles can appear on my way? |

|

Age:

Gender:

Source: adapted from Stellenbörse für MFA und Arbeitgeber (n.d.) and Psychometrics Canada Ltd. (n.d.).

12.4.3 Self-assessment sheet: Social skills and personal values

This questionnaire is suitable for pre and post measurement of a participants’ social competences and attitudes to assess their progress in the project. It should however be noted that self-assessment questionnaires are not the only tools for measurement of progress as they may be subjective and sometimes the change measured in this kind of tools may show a decrease only because the trainings made the beneficiary aware of his/her weaknesses in particular area. However, self-assessment can be complemented by other forms of external assessment done by project staff (for instance trainers, mentors, psychologists).

Table 14: Self-assessment sheet to assess social skills and personal values

Name, first name:

Date:

|

++ |

+ |

0 |

– |

— |

| Social skills |

|

|

|

|

|

| Communication skills |

|

|

|

|

|

| I pay close attention to what and how others say something. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Others tell me that I understand them well. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Even in larger groups I can express my opinion in a way that is understandable for everyone. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Team spirit |

|

|

|

|

|

| It is important to me that a team works well: that is why I share important experiences and knowledge with my team colleagues. |

|

|

|

|

|

| But I also like it when I can learn from others. |

|

|

|

|

|

| If it is important for the group, I can put my personal interests last. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I actively participate in group work, e.g. by considering how best to divide the work. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ability to deal with conflicts |

|

|

|

|

|

| Before I get too upset about something, I prefer to talk about things in a quiet minute and in a calm mood. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I have no difficulty with it when other people have a different opinion than I do. |

|

|

|

|

|

| In conversations I can easily tell whether it is a factual problem or whether two people personally do not get along well with each other. |

|

|

|

|

|

| When conflicts arise, I mediate or work towards a solution that all parties can live with (I don’t just want to win myself). |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ability to take criticism |

|

|

|

|

|

| If someone criticizes my performance or even individual behaviour, I think about whether they could be right. |

|

|

|

|

|

| If I have something to criticize about someone else, I explain it very specifically in a friendly tone. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I understand that other people sometimes make mistakes. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Dealing with people |

|

|

|

|

|

| I like to approach other people. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I usually remain calm and objective even when other people get on my nerves. |

|

|

|

|

|

| If I notice that someone else is getting upset, I can calm them down. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Personal values |

|

|

|

|

|

| Reliability |

|

|

|

|

|

| I always arrive punctually for appointments. |

|

|

|

|

|

| If I cannot keep an appointment, I apologize in time. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I always deliver work orders on time. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I don’t need to be constantly monitored: if I have a task, I think about fulfilling it myself. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sense of responsibility |

|

|

|

|

|

| Of course, I take responsibility for what I do. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I already take care of my health. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I am very careful not to put anyone in danger. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I handle the equipment or materials entrusted to me with great care. |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: adapted from Stellenbörse für MFA und Arbeitgeber (n.d.) and Psychometrics Canada Ltd. (n.d.).

12.4.4 Questionnaire for self – assessment of own competences

This questionnaire is suitable for pre and post measurement of a participants’ progress in the project. It should however be noted that self-assessment questionnaires are not the only tools for measurement of progress as they may be subjective and sometimes the change measured in this may show a decrease only because the trainings made the beneficiary aware of his/her weaknesses in particular area.

+++ is particularly true; ++ is true; + is less true.

Table 15:Self-assessment sheet to assess own competences

| 1.Self-Competence |

+++ |

++ |

+ |

| Independence |

|

|

|

| I make my own decisions |

|

|

|

| I form my own opinion and represent it |

|

|

|

| I take responsibility for my actions |

|

|

|

| I plan and carry out a work without external help |

|

|

|

| I call for outside help – if necessary |

|

|

|

| I can assert myself |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Flexibility |

|

|

|

| I can adapt to new situations |

|

|

|

| I can do different tasks side by side |

|

|

|

| I am open for new or unusual ideas |

|

|

|

| I can easily switch from one task to another |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Creativity |

|

|

|

| I find solutions for problems |

|

|

|

| I can help myself |

|

|

|

| I try out new possibilities |

|

|

|

| I have imaginative ideas |

|

|

|

| I can achieve a lot with little means |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Social Competence |

|

|

|

| Communication skills |

|

|

|

| I express myself clearly in spoken and written form |

|

|

|

| I ask if I do not understand something |

|

|

|

| I can listen |

|

|

|

| I do not judge and interpret hastily |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ability to handle conflicts |

|

|

|

| I can say no |

|

|

|

| I accept other assessments |

|

|

|

| I can offer constructive criticism and react appropriately to criticism |

|

|

|

| I recognize tension and can talk about it |

|

|

|

| I can deal with my strengths and weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ability to work in a team |

|

|

|

| I accept decisions made |

|

|

|

| I work out a solution together with others |

|

|

|

| I can also stand back in a group |

|

|

|

| I share responsibility for work results |

|

|

|

| I can take responsibility in the group |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. methodological competence |

|

|

|

| Learning and working technique |

|

|

|

| I know where and how I can obtain information |

|

|

|

| I can concentrate well |

|

|

|

| I have perseverance |

|

|

|

| I divide my strengths correctly |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Work organisation |

|

|

|

| I create a work plan and control it |

|

|

|

| I recognize connections in my work |

|

|

|

| I foresee consequences and can estimate them |

|

|

|

| I recognize the essence of a thing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4. professional competence |

|

|

|

| Expertise |

|

|

|

| I know technical terms |

|

|

|

| I know the rules and norms of my work |

|

|

|

| I have technical / linguistic knowledge |

|

|

|

| I have a good general education |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Practical knowledge |

|

|

|

| I implement specialist knowledge |

|

|

|

| I carry out work properly |

|

|

|

| I bring in what I have learned |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total |

|

|

|

Source: adapted from Stellenbörse für MFA und Arbeitgeber (n.d.) and Psychometrics Canada Ltd. (n.d.).

12.4.5 Tests used to measure skills development

There are a number of tests that have been already developed and can be utilized to help in the evaluation of entrepreneurial skills of Youth Entrepreneurship Support Actions beneficiaries (start-up founders). Measuring the skills of your participants helps you in planning and optimising your project.

These psychometric tests were inspired by tools available at the platforms mfa-jobnet.de and Psychometrics (visit www.mfa-jobnet.de and https://www.psychometrics.com) and with necessary modifications to fit this evaluation module, however the original source entails more tests that can help you assess the employability of a candidate.

Below we provide some tests you can use:

- Inspire test,

- Awareness test,

- Skills test.

- Networking test.

Inspire Test (IT)

Every entrepreneurship project has different requirements for its successful execution, and the IT allows a beneficiary to specify the importance of the personality match for the project that is being rolled out by the organization and the ideal scores that they should receive. These ratings are then used to examine how well a beneficiary’s project fits with the requirements of the whole project activity.

IT is performed by way of either personal interviews or practical exercises in teams.

Benefits of the IT

The IT provides a comprehensive measure of a participant’s personality, showing how they will:

- Complete their project,

- Interact with people,

- Solve problems,

- Manage change and,

- Deal with stress.

Sample Interview questions

ENERGY AND DRIVE

Energy

- Tell me about a project you previously worked on that required a lot of energy and commitment. What were your responsibilities? What was the end result?

- Name some of the most demanding things you have done. How did you manage them?

- Everyone runs out of energy at some point, tell me about a time when you had to work on a task that was too demanding. What did you do? What happened in the end?

Ambition

- Tell me about a time when you needed to compete hard to be successful.

- Tell me about some difficult goals you set for yourself, and how you reached them.

- Describe a situation in which you adopted a non-competitive attitude in order to be successful.

- Have you ever had a project with little room for advancement? What was that like for you?

Leadership

- What experience have you had with leading people? What was that like for you? What was positive about the experience? What would you do differently? How could you have been a more effective leader?

- Tell me about a time when you needed to convince people to follow you. What did you do? Were you able to get people onboard?

- Tell me about an occasion when you encountered difficulties with your team. What were the difficulties and how did you overcome them?

- Name a time when you took on a leadership role without being asked.

- Give me an example of a difficult leadership role you took on.

- Tell me about a time when you had to follow someone else’s lead.

IT process:

Tests will create benchmarks for the project. A beneficiary’s performance will be assessed, and a beneficiary report will be made.

- Create Benchmarks – observers will work with beneficiaries to create benchmarks for the project activity. One of the most effective ways to identify these requirements is to gather information from people who know the project well. These individuals who are familiar with the project and can speak about the knowledge, skills, and characteristics necessary for someone to emerge successful in the project.

- Assess participants – use an assessment tool to administer participant assessments.

- Assess Person – after participants have completed the Inspire module test the observer can generate a report which will indicate how well the participant’s personality traits match with the requirements of the project activity.

The IT report does provide among others; Overall project activity fit score – which is quickly sorted based on the candidates overall fit with project benchmarks, Participant profile that helps identify participants’ specific areas of fit or misfit,

In-depth narrative description of the participant’s shared working space behaviours, helping to target areas of uncertainty in follow-up interviews and

Profile validity – assesses the extent to which the questionnaire was completed honestly rather than in an overly positive or unusual way.

Source: adapted from Stellenbörse für MFA und Arbeitgeber (n.d.) and Psychometrics Canada Ltd. (n.d.).

Awareness test (AT)

Youth Entrepreneurship Support Actions have the goal of developing entrepreneurial skills. Therefore, the objective of this test is to provide overview of the different competences and soft skills that are to be developed with the measures to be evaluated and the skills to be tested.

- Self-management – Readiness to accept responsibility, flexibility, resilience, self-starting, appropriate assertiveness, time management, readiness to improve their team’s performance based on feedback and reflective learning.

- Team working – Respecting others, cooperating, negotiating, persuading, contributing to discussions, awareness of interdependence with others.

- Cultural tolerance / sensitivity – being able, respecting people of other cultures, not discriminating against people of other cultures.

- Business and customer awareness – Basic understanding of the key drivers for business success and the importance of providing customer satisfaction and building customer loyalty.

- Critical thinking – collecting and analysing information objectively, making a reasoned judgment.

- Problem solving – Analysing facts and circumstances to determine the cause of a problem and identifying and selecting appropriate solutions.

- Communication – The ability to effectively tailor messages for the purpose and audience and use the best tools available to communicate them.

- Time management – Ability to plan and organise one´s time among different activities.

- Flexibility – Ability to work within permanently changing environment and desire to look for win-win solutions.

- Resilience – Ability to work under pressure.

- Efficiency – Applying the 80/20 rule and other techniques for yielding higher results in less time. Switching between different chores and progressing effectively day-to-day.

- Networking – Growing a network facilitates business opportunities, partnership deals, finding subcontractors or future employees. It expands the horizons of PR and conveying the right message on all fronts.

- Branding – Building a consistent personal and business brand tailored to the right audience.

- Sales – Being comfortable doing outreach and creating new business opportunities. Finding the right sales channels that convert better and investing heavily in developing them. Building sales funnels and predictable revenue opportunities for growth.

Helping a beneficiary in understanding their personality type is the first step to personal and entrepreneurial growth. The AT helps beneficiaries to understand their strengths, their preferred working styles, and ultimately helps them see their potential. Used individually to provide self-awareness and clarity of purpose, the AT also helps to create a better understanding and appreciation between their teams – enabling them to work better together.

AT can be performed in either personal interviews or practical exercises in their teams.

Benefits of the AT:

- Greater understanding of oneself and others.

- Improved communication skills.

- Ability to understand and reduce conflict.

- Knowledge of your personal and work style and its strengths and development areas.

Interview questions

SOCIAL CONFIDENCE

If the project requires an individual to be self-assured and at ease with people in all types of social situations, consider some of the following questions:

- Give me an example of a time when you had to interact with a group of strangers for a work-related function. What did you do? What was the result?

- Tell me about a time when you had to exercise social confidence to accomplish a goal.

PERSUASION

If the project requires someone who is comfortable with negotiating, selling, influencing and attempting to persuade people or trying to change the point of view of others, consider some of the following questions:

- Give me an example of a time when you persuaded someone to purchase something? What did you to do convince them?

- Tell me about a time where you changed someone’s mind. What did you do/say that made them see things your way?

- Name a time when you used negotiating to get what you wanted. What was the result?

INITIATIVE

If the project requires someone with a high level of initiative to identify new opportunities and take on challenges, consider some of the following questions:

- Give me an example of a time when you completed a project without any support from others. What was the outcome?

- Tell me about an opportunity you identified that others missed.

- Describe some new challenges that you took on without encouragement from others.

- Name some new responsibilities you took on voluntarily.

- When you identify a potential opportunity what do you need before you will begin working towards it?

- What do you prefer, stable project responsibilities or frequently changing responsibilities, and why?

- Tell me about some occasions where you have shown initiative.

- Give me some examples of when you have shown initiative.

Source: adapted from Stellenbörse für MFA und Arbeitgeber (n.d.) and Psychometrics Canada Ltd. (n.d.).

Soft-skills test (SST)

This test demonstrates the difficulty in developing the competences listed in awareness test and consequently propose specific knowledgebase (lessons) that can do this.

The SST is used to help participants and their team members get acquainted with each other’s conflict styles, identify potential challenges, and set goals for how they should handle conflict as a group. With established teams, the SST helps team members make sense of the different conflict behaviours that have been occurring within the team, identify the team’s challenges in managing conflict, and find constructive ways to handle those challenges.

SST may be performed either as personal interviews or practical exercises in teams.

The SST describes five different conflict modes and places them on two dimensions:

- Assertiveness – the degree to which a person tries to satisfy their own needs

- Cooperativeness – the degree to which a person tries to satisfy other people’s needs.

Benefits of the SST

Why do organisations use the SST?

- It is easy to complete, the short questionnaire takes only a few minutes and can be administered online before your training or in paper booklet onsite.

- Delivers a pragmatic, situational approach to conflict resolution, change management, leadership development, communication, participant retention, and more.

- Enables your organisation to open productive dialogue about conflict.

- Can be used as a stand-alone tool by individuals, in a group learning process, as part of a structured training project workshop.

Interview questions

DEPENDABILITY

If you are looking for participants (beneficiaries) with a high level of dependability, consider some of the following questions:

- Tell me about a project you couldn’t finish on time. What happened? What would you do differently?

- Are you comfortable leaving a project unfinished if something else comes up?

- Give me an example of a task that you needed to work beyond your normal hours to complete. What was that experience like?

- Can you describe a time when you had to shift priorities and leave a task you were working on unfinished? What happened? How did you complete the first task?

- Name a time where it was difficult for you to complete your task. What happened, and how did you resolve the difficulties?

- Describe a time when you needed to work extra hard to get your tasks done on schedule.

PERSISTENCE

If the project requires someone with a high level of persistence, consider some of the following questions:

- Tell me about a difficult task that you recently completed. What made it difficult? How did you manage to work through the difficulties/obstacles?

- Describe a time when you had a large number of boring/dull/uninteresting tasks to complete. How did you motivate yourself?

- Give me an example of a project that you gave up on because it was no longer worth the resources to complete.

- Tell me about a time when you showed a high level of persistence.

- Tell me about some obstacles you have overcome that took a lot of persistence.

- Give me an example of something you gave up on because you did not think it worth the effort.

If the project mostly involves tasks that can be completed quickly and has few obstacles to overcome, consider some of the following questions:

- Give me an example of a project that you gave up on because it was no longer worth the resources to complete.

- Describe a time when you had a lot of boring work to complete. How did you motivate yourself?

- Have you ever worked on a project that only required you to do easy work that had no challenges? What was that like for you? Was it pleasant or unpleasant?

ATTENTION TO DETAIL

If the project involves tasks that require a lot of detailed information or research, consider some of the following questions:

- Describe a project you worked on that involved a lot of detailed work.

- What is the most detailed work you have had to complete?

- What is worse for you, completing a project late, or completing it on time with imperfections?

- What kind of tasks have you had to do in the past that required you to pay close attention to details?

If the project does not involve examining a lot of detailed work, but requires someone who focuses on global problems, best practices or issues, consider some of the following questions:

- Tell me about a time when you ignored the details and focused on the big picture.

- Tell me about a time when people on your team focused too much on details and missed the big picture. What did you do to help them broaden their focus? Is there such a thing as spending too much time looking at the minor details?

- What experience do you have with determining strategy/looking at the big picture/setting large goals and priorities?

RULE-FOLLOWING

If the project has a lot of operational procedures and rules that need to be strictly followed, consider some of the following questions:

- Describe your past experiences of working in a very structured, rule bound environment.

- Describe your experiences of working in an environment with no structures or rules on how to work.

- Can you tell me about an occasion where you needed to ignore rules or procedures to get your work done successfully?

- How do you determine when to ignore procedures/rules? Are there situations where you believe they should be followed all the time? How do you determine when that is?

If the project has few to no procedures and rules, and requires the individual to determine the best way to complete their tasks, consider some of the following questions:

- Tell me about some ineffective rules that were still followed in your previous innovation centre or business incubator.

- Can you tell me about an occasion where you needed to ignore rules or procedures to get your tasks done successfully?

- How do you determine when procedures/rules can be ignored? Are there situations where you believe they should be followed all the time? How do you determine when that is?

- How often do you encounter rules/procedures that you think should no longer be in effect?

- How comfortable are you working on tasks when you have not been given any direction/instruction? Do you enjoy the freedom? Do you wish you could get feedback to ensure you are doing your tasks correctly?

PLANNING

If the project involves a lot of short and long-term planning, consider some of the following questions:

- Tell me about a task you completed that required a significant amount of planning.

- Give me an example of a long-term goal or plan that you established. Did you meet your goals? How effective was your plan?

Source: adapted from Stellenbörse für MFA und Arbeitgeber (n.d.) and Psychometrics Canada Ltd. (n.d.).

Networking test

The main objective here is to improve Youth Entrepreneurship Support Action’s networking activities and knowledge exchange, enabling the setting up of successful innovation ecosystems across Europe.

Benefits of the NT?

- It links your interests and preferences to various task activities, project settings and careers.

- The NT gives you results that you can benefit from if you are just starting out in your business.

NT is done either by way of personal interviews or practical exercises in teams.

Interview questions

PROBLEM SOLVING STYLE

INNOVATION

If the project requires someone who is creative and innovative, consider some of the following questions:

- Tell me about a problem you solved in an innovative way.

- Name an original/creative/new solution you came up with to solve a problem.

- When addressing a problem do you first look at what was tasked in the past, or do you come up with an entirely new solution?

- What are the benefits/disadvantages of using past solutions?

- What have been some of your most creative ideas at task?

- When you don’t understand something, do you ask until you understand?

- Do you often question what is considered normal?

- Do you like to watch people? Do you often question what is considered normal?

- Do you like to watch what is happening in the world as part of innovation?

- Do you observe how people behave in situations that may affect you start-up (e.g., where, and how to eat, drink, dress, shop, etc.). Do you observe the world around you? Do ideas for new products and services come to mind?

- Are you adventurous, happy and looking for new experiences?

If the project does not require much problem solving, or the problems addressed only require incremental changes or practical solutions, consider some of the following questions:

- When addressing a problem do you first look at what has tasked in the past, or do you come up with an entirely new solution?

- What value do you see in sticking with the established ways of doing a task?

- What are the benefits/disadvantages of using past solutions?

- What have been some of your most practical solutions to task problems?

- Would you describe yourself as innovative or practical?

ANALYTICAL THINKING

If the project requires analysing a large amount of information and a decision-making approach that is logical, cautious, and deliberate, consider some of the following questions:

- How much information do you need to feel comfortable making a decision? How do you get that information?

- Tell me about a decision you have made through extensive information gathering and discussion with others. How did it work out? Did you need to be as cautious as you were, or could you have made the decision more quickly?

- Would your friends describe you as analytical and calculating or intuitive and spontaneous? Why?

- What process do you go through before you make a decision?

- Tell me about an important decision you needed to make quickly.

If the project requires quick decision making that does not allow for the extensive gathering of information, consider some of the following questions:

- How much information do you need to feel comfortable making a decision? How do you get that information?

- Tell me about a decision you have made based on your gut feelings. How did it task out? How comfortable are you making decisions that way?

- Would your friends describe you as analytical and calculating or intuitive and spontaneous? Why?

- When have you had to rely upon your intuition to make a decision?

DEALING WITH PRESSURE AND STRESS

SELF-CONTROL

If the project requires the individual (beneficiary) to have a high level of self-control, consider some of the following questions:

- What do you do when you get frustrated with others? Tell me about a time when you were frustrated with a team member.

- Give me an example of when you maintained your composure in a difficult situation.

- Give me an example of a time when you were angry with someone at task. What did you do?

- Describe a previous task experience that had you frequently dealing with upset people.

- What experience have you had dealing with irate customers?

- Tell me about a time when you had to deal with an upset customer. What did you do? What were the results? How did you feel afterwards?

STRESS TOLERANCE

If the project requires regular results in a high level of stress, consider some of the following questions:

- What do you do to alleviate stress?

- How do you tolerate stress?

- Name a time when you had to do a task under extreme stress.

- What types of activities do you find stressful?

- Name a time when you had difficulty coping with stressful tasks. What did you do to get yourself through that time?

- What type of stress do you find very hard to deal with?

- Are there stressful activities that you cannot cope with? What are they?

- What do you find to be the most stressful?

- What kinds of extreme stress have you had to execute tasks under?

- What have been some of the most stressful things you have been involved in?

Source: adapted from Stellenbörse für MFA und Arbeitgeber (n.d.) and Psychometrics Canada Ltd. (n.d.).

12.4.6 Business Model Canvas

The Business Model Canvas is a good tool for assessing a start-up at the beginning and end of the project – to measure business development.

Figure 9: Business model canvas

Source: Strategyzer, n.d.

Summary of steps on how you could use the business plan format in assessment of Entrepreneurship Project Actions:

Development of a business/ project idea from the point of view of a start-up

- Which idea/ plan is working best for me?

- What makes it different from others?

Requirements of the founder

- What are my qualifications, strengths, and weaknesses?

- Which partners do I have, or do I need?

Overview over the market

- What is my target group and what do these people need?

- What do my competitors offer?

Good strategies for marketing and distribution

- How could good advertisement look like?

- What is my distribution area and roads?

- Do I have a good price strategy?

Set up of the organisation /company

- How many employees do I need and what should their skills/ qualifications be?

- How does the legal form of my company look like?

Analysis and weighing up of the possible chances and risks

Financing

- How much are my potential customers willing to pay?

- How high are my capital requirements?

- Do I have a financing- and investment plan?

- Are there alternative funding opportunities? Grants, donations.

- How high are my costs of living?

Acquisition of further documents

- Do I need other documents, for example expert opinions, contracts or curriculum vitaes?

- Legal requirements?

Want to try it on your own? Fill the Business Model Canvas here below.

Figure 10: Template of a Business model canvas

Source: Strategyzer, n.d.

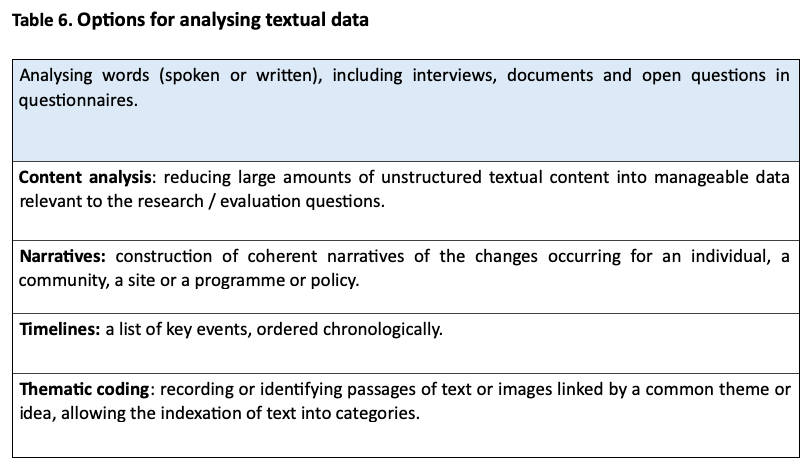

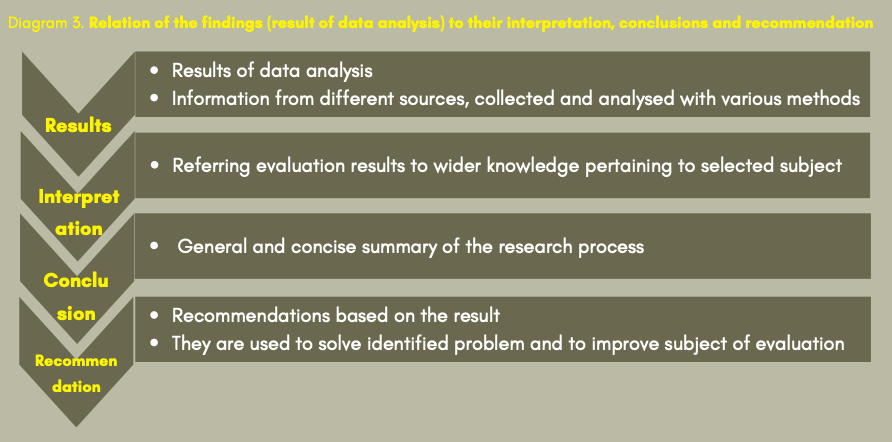

12.5 Tools to use in Analysing Information

Below are some tools you could use in analysing the information that you have gathered above.

12.5.1 Assessing the outcomes (‘the what’) of your project

The questions below are provided simply as guidance in assessing the outcomes of your project.

You may have additional or different questions you want to ask depending on the nature of your project and your reason for evaluating.

- In what ways have participants benefited from being in your project? (e.g., re-engaged with learning, gained accreditation, increased or improved industry specific networks, identified a realistic vocational pathway, gained entrepreneurship skills, gained identity documents etc.)

- How do you know this? (That is, what information or evidence do you have to show that the participants have benefited?)

- What other benefits have you delivered (and to whom)?

- Have there been any surprising or unanticipated outcomes?

- How do you know if it is your project that is making the difference? (i.e. there might be other things that are going on in the organisation at the same time as your project which might also impact on participants’ outcomes or things you are trying to measure).

12.5.2 Assessing the effectiveness (‘the how’) of your project

The checklist below is provided as a simple way of assessing the effectiveness of the project (‘the how’) and to identify potential areas for improvement.

You may have additional or different questions you want to ask depending on the nature of your project and your reason for evaluating.

Table 16: Checklist for assessment of the effectiveness of a project

| Key Question |

Y/N |

Examples of Follow Up (To address identified issues) |

| Are all stakeholders wholly engaged in the project? |

No |

Arrange a meeting of all stakeholders to review current levels of involvement and see if this needs to change and in what ways. For example, are more resources needed? Would formalizing the project in a memorandum of understanding make a difference? If there is a genuine lack of engagement from one partner and this is unlikely to change, should the support of another organisation be sought? |

| Is there a shared vision and common goals? |

|

Create a kind of glossary in joint work – in which the goals are defined, and a common interpretation is fixed. |

| Does each stakeholder have a clearly defined role and responsibilities? |

|

Create a kind of organigram in which each party is represented with its roles & responsibilities – this should be accessible to all. |

| Are the expectations of each stakeholder fair and reasonable? |

|

|

| Does each stakeholder have a good understanding of requirements of other stakeholders? |

|

|

| Is there regular communication between stakeholders? |

|

|

| Have all parties received fair recognition for their efforts? |

|

|

| On balance, have the benefits of the collaboration justified the time and effort that have gone into it? |

|

|

It can help to break down an overarching or key evaluation question into a small number of sub questions to guide the information gathering and analysis. The table below shows how one project Entrepreneurship training for unemployed graduates went.

Table 17: Checklist to assess an Entrepreneurship training for unemployed graduates

Name of Project: Entrepreneurship training for unemployed graduates.

| Objective |

Focus of the evaluation |

Evaluation question |

Questions included in evaluation tools (asked to interviewees/ respondents) |

| To help participants turn their ideas into operational and profitable businesses. |

Focus on the impact of the activities or project (the ‘what’). |

How, and to what extent, has the project helped graduates to turn their ideas into operational and profitable businesses? |

» What knowledge and skills have been gained by participants through this project?

» How have these skills helped participants in their quest to turn ideas into fully fledged businesses?

» Are there other things that could be done to support participants in their quest?

» What additional information is needed to make a decision about the future of the project. |

| To identify how well the stakeholders are working together and if improvements could be made. |

Focus on the effectiveness of the projects (the ‘how’). |

How effective are our current projects? |

» What are we doing well?

» What are the things that are not working so well?

» How can we improve these projects? |

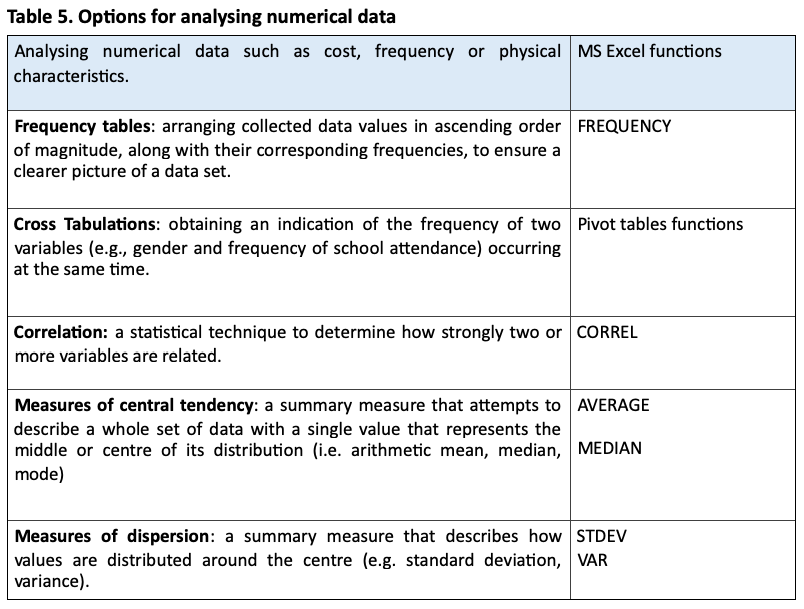

12.5.3 Quantitative analysis techniques

Figure 11: Overview if quantitative analysis techniques

Source: Cottage Health, n.d.

12.5.4 How to present quantitative data

Table 18: Overview of data presentation formats

| What do you want to present? |

Which chart to use |

| Comparison of two or more categories |

Bar chart, circle chart |

| Binary date (e.g. yes/no responses) |

Pie chart, bar chart |

| Change over time |

Line graph, area graph |

| Correlation between two variables |

Scatter graph |

| Frequency |

Bar chart |

| Percentages |

Bar chart, pie chart |

| Dispersion (how spread out your date set is) |

Box and whisker plot, bar chart |

Source: The National Council for Voluntary Organisations, n.d.

12.5.5 Tools to use when using information

Having a clear structure makes your report easier to read. Before you write, plan your headings and subheadings such that your report is easily comprehensible and legible. You can find a sample structure of an evaluation report here below:

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABBREVIATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION

-

- Project background, source of financing, partners/ stakeholders, target group and participants, process of implementation, objectives, activities/tasks and results

1.2 Evaluation concept – type, scope, purpose, criteria and questions

METHODOLOGY

2.1 Methods of collecting information, and samples

2.2 Reliability and validity issues

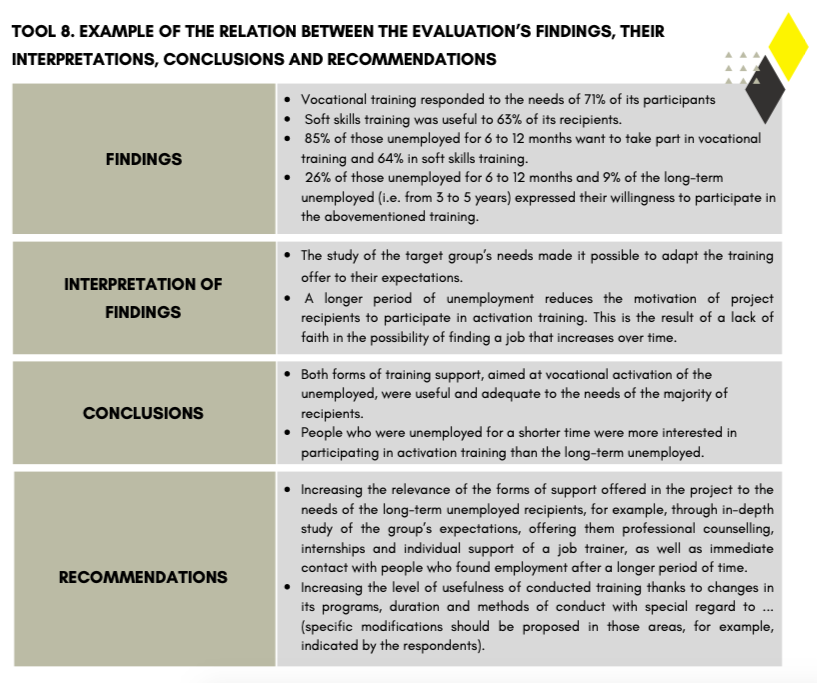

RESULTS

3 They should be discussed according to the evaluation criteria and questions

LESSONS LEARNT, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

4.1 Lessons Learnt

4.2 Conclusions and recommendations

ANNEXES

Annex 1: Map of the intervention area

Annex 2: Research tools (e.g. questionnaires and scenarios used)

Figure 2: Evaluation of Youth Entrepreneurship Support Actions Life Cycle – Phase 1

Figure 2: Evaluation of Youth Entrepreneurship Support Actions Life Cycle – Phase 1